A Variety of Ice in the Krossfjorden at Lilliehookbreen Glacier

Bergy bit has to be my favorite new term from the expedition. What is a bergy bit you ask? Before I define bergy bit, know that in an area where ice is prevalent, there will inevitably be a plethora of words to describe it. To help build knowledge of this cold climate phenomenon I purchased, A Field Guide To Ice, which provides 84 definitions for ice and snow as well as what they leave behind in their frozen wake. Page seven describes ice bergs and this is where bergy bits come in. According to the guide written by James H C Fenton, a bergy bit is, “as icebergs, but smaller, with 3-15 feet above water.” That is between a child’s height and a bit taller than the average ceiling.

Bergy bits are smaller than ice bergs, and growlers are smaller than bergy bits with just 3 feet above the surface. Brash ice are even smaller pieces of ice. Bergy bits, growlers, and brash ice can begin as ice bergs and melt down over time. As I watched the Lilliehookbreen glacier calve I observed varying sizes of ice falling into the water, some pieces appeared to be bergy bits. I just love saying bergy bits. It makes me smile. Try it. It sounds like a kid’s breakfast cereal!

Iceberg next to the Austfonna Ice Cap – Photo courtesy of Fiona Hall

Icebergs, bergy bits larger cousins, begin when a glacier, ice cap, ice sheet, or ice shelf calves. This is when a piece of ice breaks off and lands in water. Calving sounds like thunder and when there is active calving it sounds like a thunder storm is right on top of you. No lightning in this storm, but watch out for the wakes and debris. While kayaking or in the zodiacs we were warned to steer clear. To be considered an iceberg more than 15 feet of ice needs to be above water with most of the iceberg hiding beneath the surface. Here is an example of a glacier calving.

Glaciers are moving streams of ice that grind up the landscape as they travel. As with all other things ice there are many types of glaciers classified by size and land constraints. Valley glaciers are within valleys, hanging glaciers are glaciers above valleys, and corrie glaciers reside in bowl shapes. Hanging glaciers and corrie glaciers are small, according to Fenton. Glaciers form when the snow accumulates faster than it can melt. Pressure compacts the snow into glacial ice and gravity pushes it downhill aided by its own weight. This timelapse video shows glacial movement of a glacier in Chile:

Glacier vs People in the Krossfjorden

Blue Ice

Have you noticed that some ice is blue? I interviewed Doug, a naturalist aboard the National Geographic Explorer, about the blue. In simple terms ice that looks blue, whether in a glacier ice berg, bergy bit, growler, or brash ice, is more dense with less air inside the ice. I learned that it takes fifty feet of compacted snow to make one foot of glacial ice. That’s a lot of compacting going on. No wonder it is so dense!

Ramesh Capturing Austfonna

Ice Caps are a particular type of glacier that cover a large area of land smaller than 50,000 km² (about 19,000 square miles). Larger than that and glaciers are classified as ice sheets. We were fortunate enough to observe the Austfonna Ice Cap while on expedition. It is one of the largest in the world at 8,492 km2. The captain steered the National Geographic Explorer along it’s edge for what seemed like forever. That’s not surprising considering the ice front along the ocean is 100 miles long. I’m sure we didn’t follow the entire edge. What we did see ranged between 50 and 200 feet in height. Breathtaking.

Melting Ice

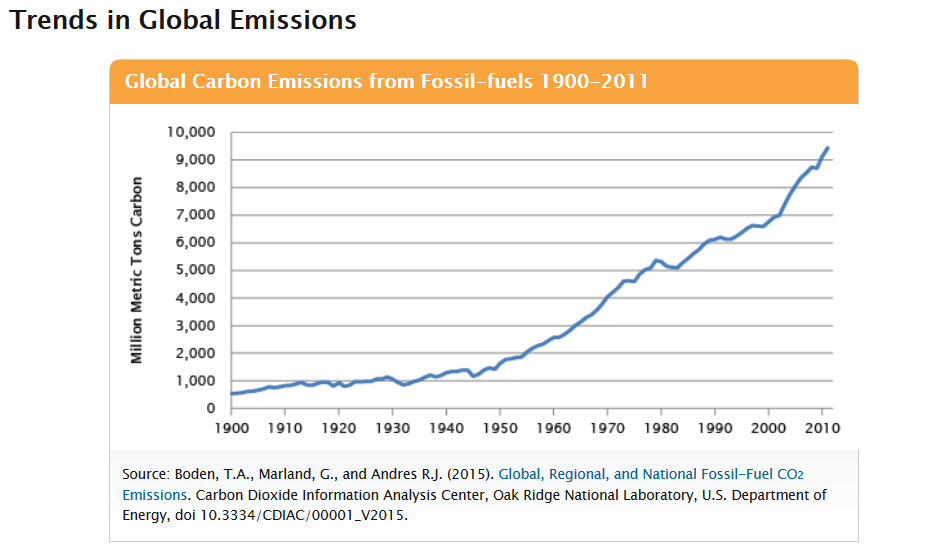

Climate change is inevitable, or at least that is what I kept hearing over and over from the naturalists, and it is affecting glaciers and sea ice, two very essential things for the wildlife in Svalbard. The earth’s climate has changed many times throughout its history. It is part of the natural system. So what makes it so different now? According to Fen Montaigne, a guest speaker on board this expedition, people are accelerating the process. Switching to renewable resources like wind turbines, solar power, geothermal, and nuclear power were his suggestions for helping to curb carbon emissions. I spoke to him later about nuclear power since I live in Washington and we are dealing with the leftover mess at the Hanford Site. He said they are making safer reactors. I’m not sure I agree with that suggestion, but the others I am all for. Here is the interview:

I snipped this graph from the EPA Website to help illustrate the situation.

I guess the question is, what can I do to make a smaller fossil fuel footprint so the polar bears can still make theirs in ice and snow where they belong?

Leave a Reply